(I’m going to give all of you a word of warning right now: You’re probably going to think this is really boring.)

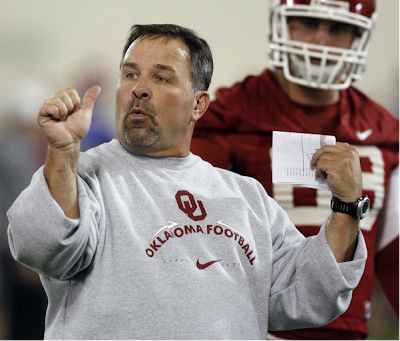

Oklahoma offensive coordinator Kevin Wilson just can’t win with second-guessing Sooner fans.

Earlier this season, Wilson’s critics–Homerism included–blasted the 2008 Broyles Award winner for refusing to air it out down in Miami against the Hurricanes. OU signal caller Landry Jones has provided a pretty resounding response to the Wilson’s interlocutors since then, tossing a total of seven interceptions in losses to Texas and Nebraska.

Now, after Jones attempted nearly 60 passes last weekend in a 10-3 loss in Lincoln, the Sunday morning quarterbacks are wondering why the Sooners didn’t keep it on the ground more.

Offensive play-calling represents one of the most frustrating, and yet least-understood, aspects of football to the average football fan.

With the benefit of hindsight, anyone can become an expert on calling plays. I mean, if it didn’t work, it was a bad call, right? Nevermind:

- matchup advantages;

- personnel strengths and weaknesses, which are ever-changing when you factor in injuries, suspensions, etc.;

- down and distance;

- “ulterior motives,” such as such as setting up a deep pass with play-action;

- time;

- score.

In that respect, the popular analogy of a chess match taking place between coaches is a vast oversimplification. In fact, making a single play call often involves exponentially more variables than your average move on the chessboard.

In that respect, the popular analogy of a chess match taking place between coaches is a vast oversimplification. In fact, making a single play call often involves exponentially more variables than your average move on the chessboard.

(There’s a great in-game scene in the second season of the television series Friday Night Lights where the director cuts furiously between rival coaches talking to their teams during a timeout before a crucial play late in a game. The fast-paced, back-and-forth shifts between the sidelines perfectly capture the move-counter-move-counter-counter-move dynamic of just one play call.)

So how can typical fans evaluate a coordinator’s performance? I’m proposing a “results-oriented” approach: whether or not a play, or series of plays, can achieve a specific objective.

How would this work? Let’s use Wilson’s calls on first downs in the Nebraska game to illustrate this approach and see if we can draw any conclusions.

You could categorize a series of plays as a success based on a whole host of metrics. In this case, let’s assume that first-down plays are successful if they generate an average of at least 3.33 yards per attempt. In theory, this puts an offense on schedule to gain another first down within three plays, i.e. avoid a fourth-down decision to punt or go for it.

OU had 40 first-down plays: 23 passes and 17 rushes. At first blush, the skew to passing so frequently seems odd. Conventional wisdom holds that teams typically prefer to run on first down, as run plays generate more consistent yardage, despite the decreased chance of a longer gain.

However, what if a team is running consistently shitty on first down?

The Sooners gained an average of 3.24 yards per rushing attempt on first down against Nebraska, slightly below the target. Yet, the individual observations suggest a small number of big plays inflated this average.

Of the 17 relevant observations, 12 went for three yards or fewer. (Note that none of these were sacks.) Thus, running on first down put OU’s offense in supposedly advantageous position on the next play five out of 17 times.

The 23 first-down pass attempts generated a per-play average of 6.35 yards, which means the Sooners typically were well ahead of schedule on the following play. Equally important, on 13 of 23 occasions, OU’s passing attempts produced at least four yards. Eight attempts yielded 11 yards or more. (It should be pointed out that Jones did throw an interception on one first-down attempt, which is, obviously, a very negative outcome.)

That means 57 percent of the time that Wilson called a pass play on first down a successful outcome resulted. Contrast that with the 29 percent hit rate on run plays.

Would the Sooners have worn down Nebraska’s defense by calling more run plays on first down, thereby gaining some kind of physical advantage? Possibly.

Would the Sooners have put themselves in worse situations on second down by running more often on first down? Possibly.

Under this rubric, though, what shouldn’t be up for debate is that Wilson’s play-calling on first down continually put the OU offense in a more advantageous position throughout the game. If anything, the numbers suggest that OU should have thrown even more frequently on first down.